-

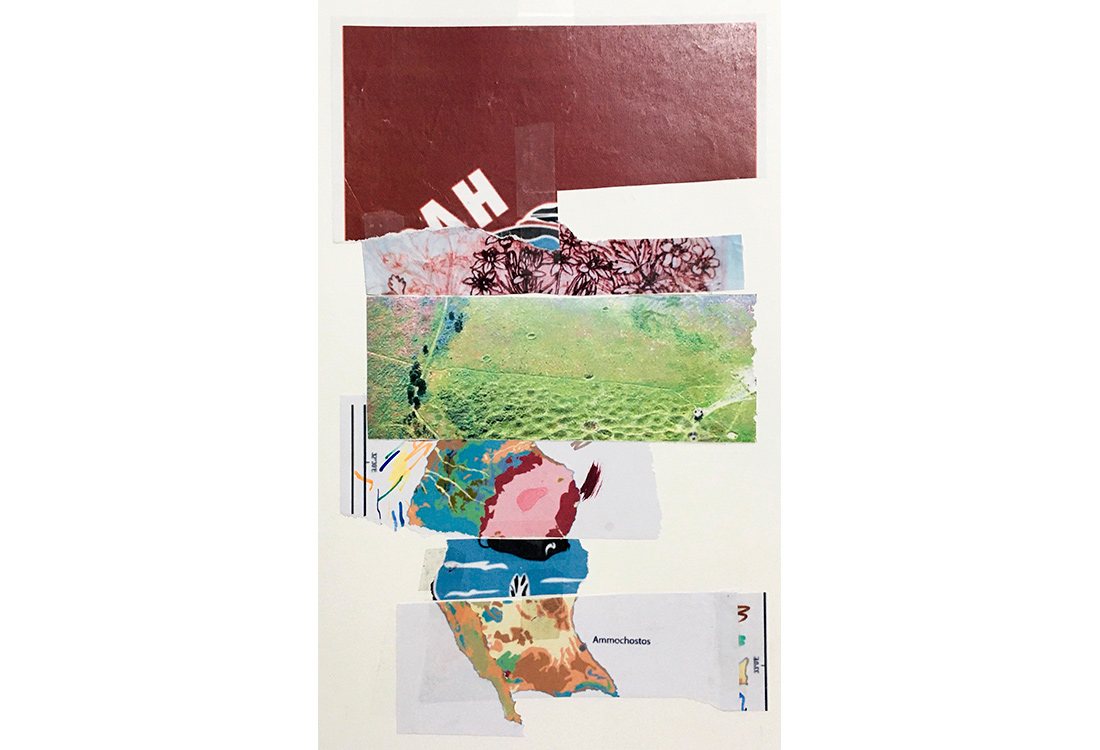

4 / 70 | Chicxalub Crater is an ancient impact crater buried underneath the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. The crater is more than 180 kilometers in diameter. The impacting bolide that formed the crater was at least 10 km in diameter. The impact associated with the crater is implicated in causing the extinction of the dinosaurs as suggested by the K-T boundary.

-

7 / 70 | The Panga ya Saidi Site, Kenya, 78,000 ya. This body was laid in a purposely funereal position. Researchers suggest that humanity’s changing attitudes towards death began to include concessions for unique circumstances, such as the death of a child or a death by accident. While most deaths would have been seen by these nomadic people as natural and even unavoidable, the death of such a young child seemed to have more significance to them. This image is a virtual reconstruction of the child’s remains who was named “Mtoto” (‘child’ in Swahili).

-

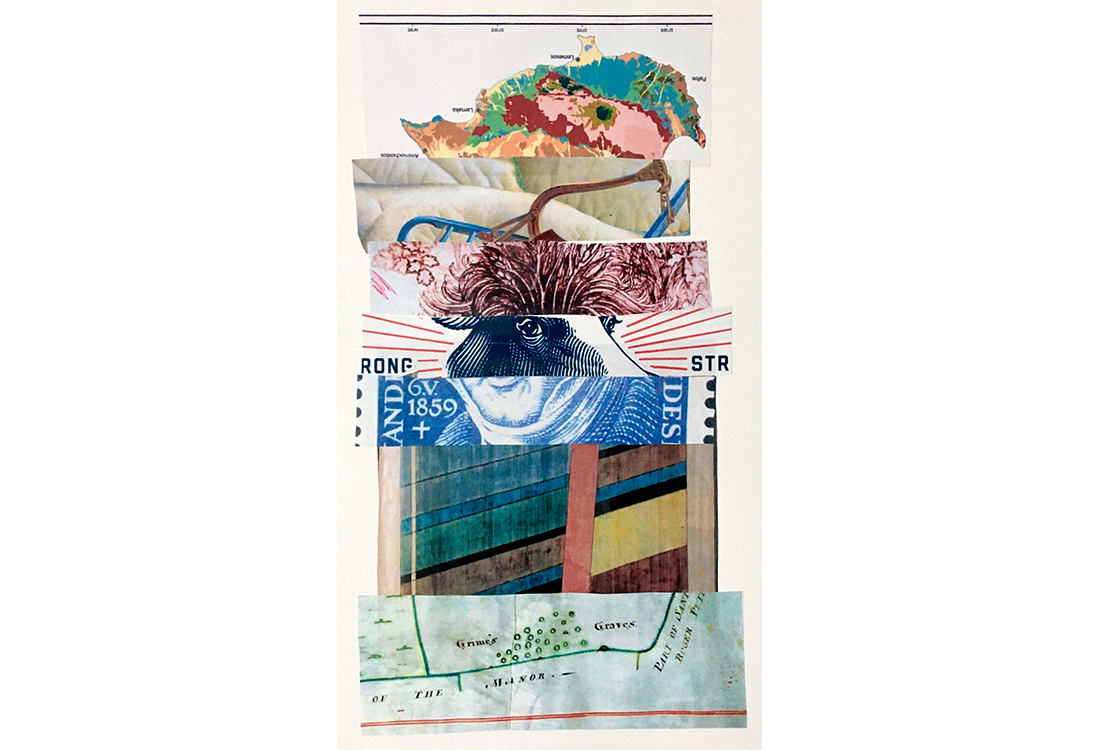

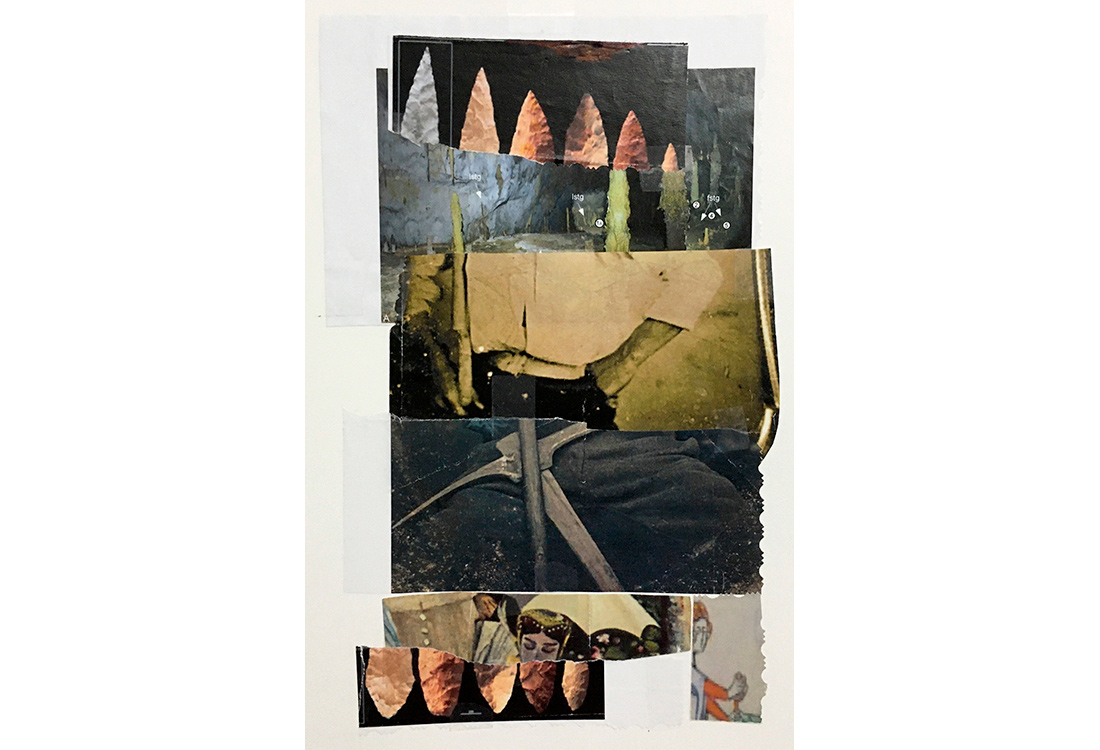

14 / 70 | Grime’s Graves is grassland pockmarked with over 430 prehistoric flint mine pits. It is one of the best places in Britain to see the links between geology and archaeology. The earliest pits were “dug” as vertical shafts in late Neolithic times, about 4,600 years ago, to reach rich seams of flint nodules. The mysterious lunar-like landscape of Grime’s Graves is the legacy of hundreds of years of activity by Neolithic flint miners, to extract the fine quality, jet-black flint from which they fashioned tools, weapons and ceremonial objects.

-

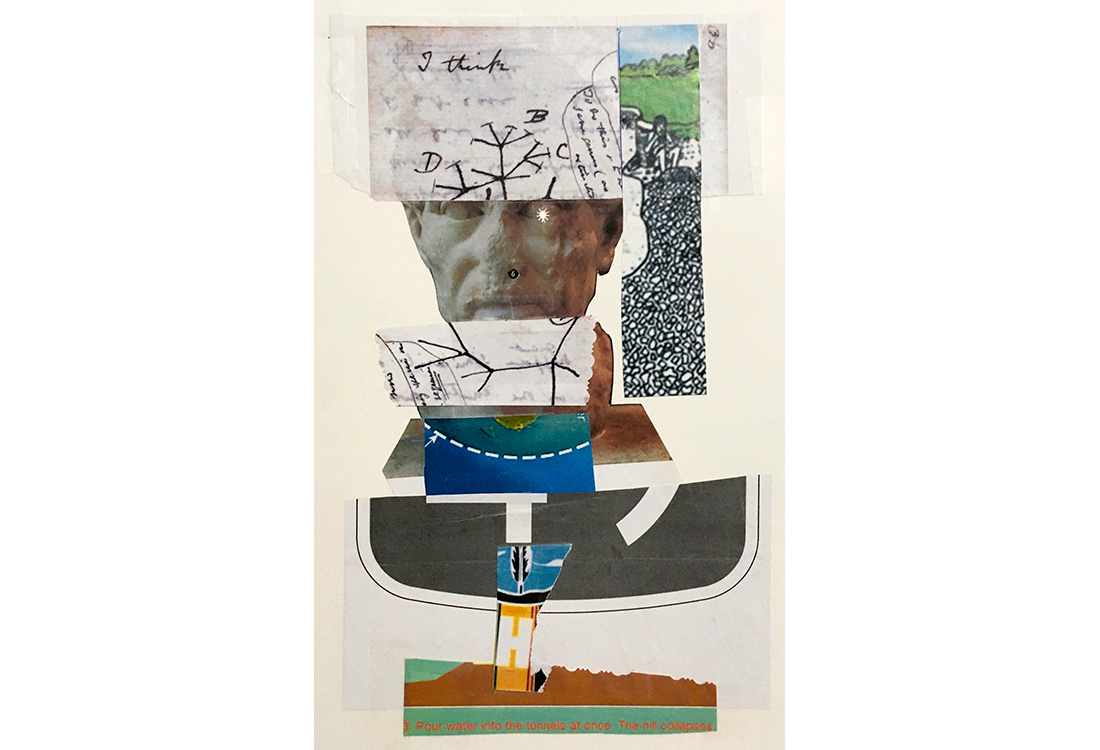

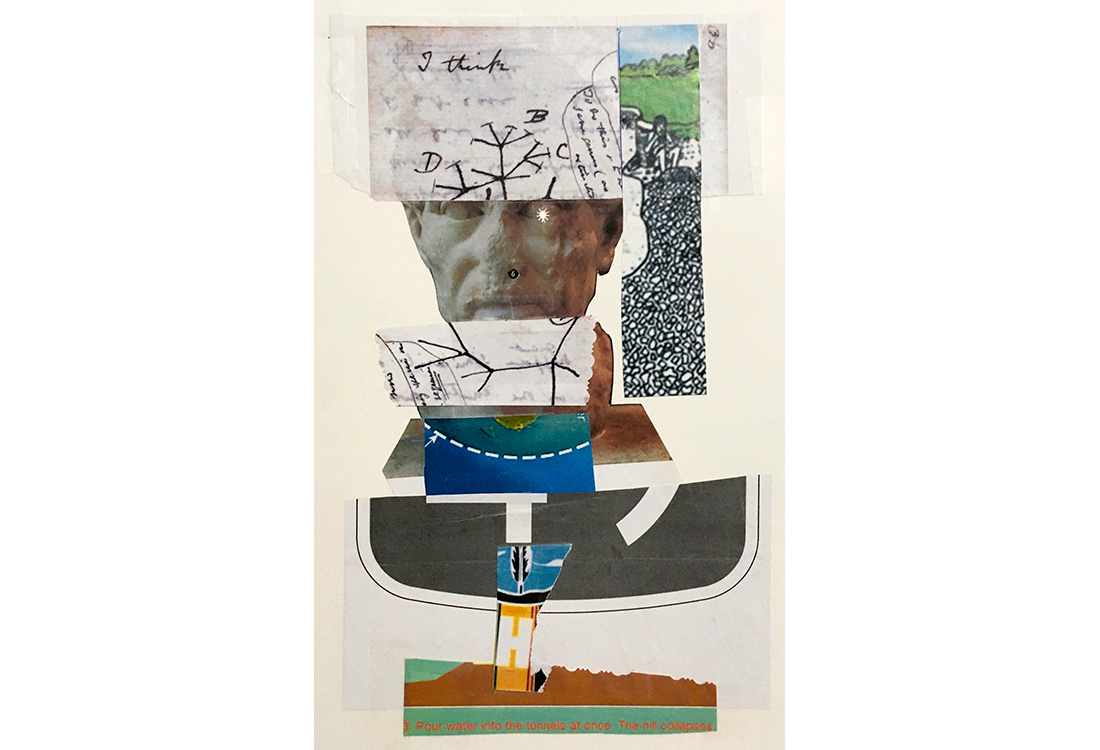

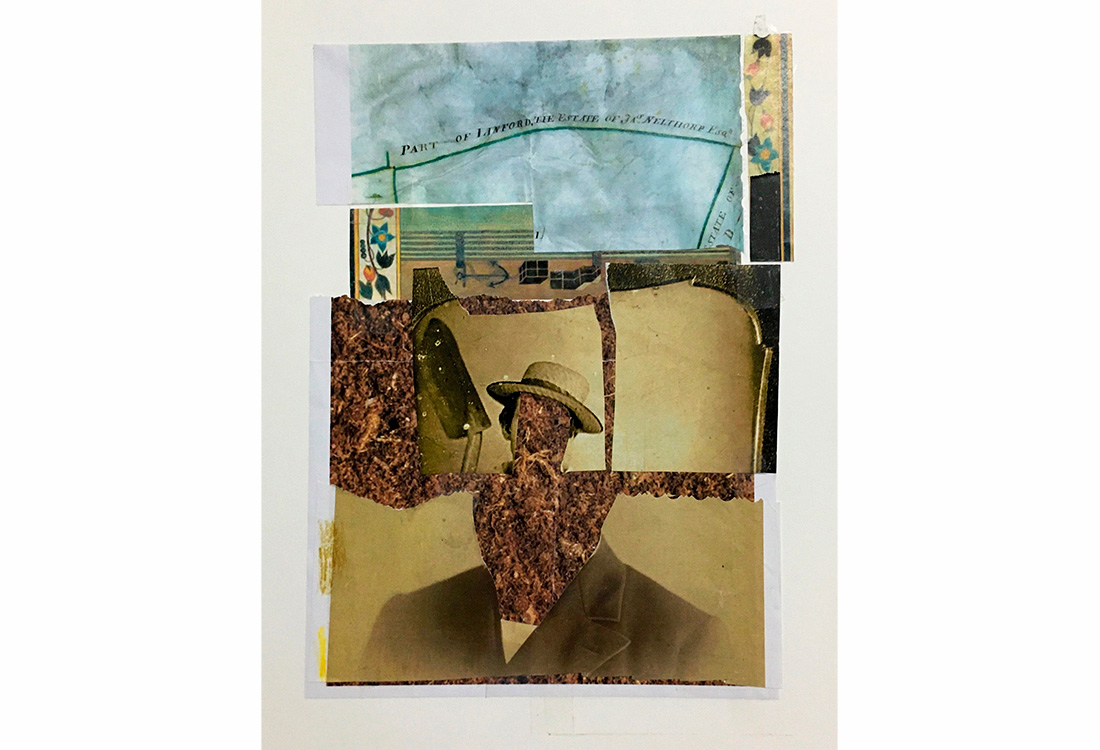

24 / 70 | Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862). Among his lasting contributions are his writings on natural history and philosophy, in which he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology and environmental history, two sources of modern-day environmentalism. “As for your high towers and monuments, there was a crazy fellow in town who undertook to dig through to China, and he got so far that, as he said, he heard the Chinese pots and kettles rattle; but I think that I shall not go out of my way to admire the hole which he made” is from his novel, “Walden”, 1854.

-

30 / 70 | Claude Monet (1840–1926) “Women in the Garden” is an oil painting begun in 1866. Monet painting its upper half with the canvas lowered into a trench he had “dug”, so that he could maintain a single point of view for the entire work. Monet remarked: “It’s on the strength of observation and reflection that one finds a way. We must dig and delve unceasingly”. In fact, his research reflects a precise and unique study of the passing of time as seen in the movement of light over forms.

-

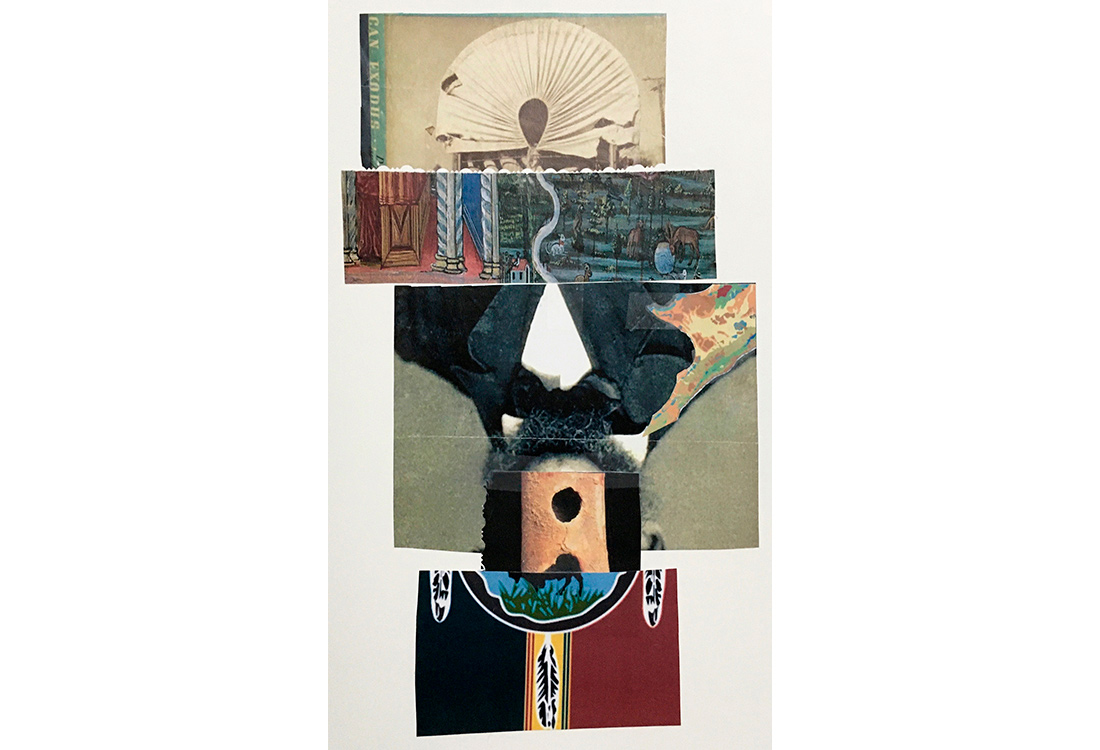

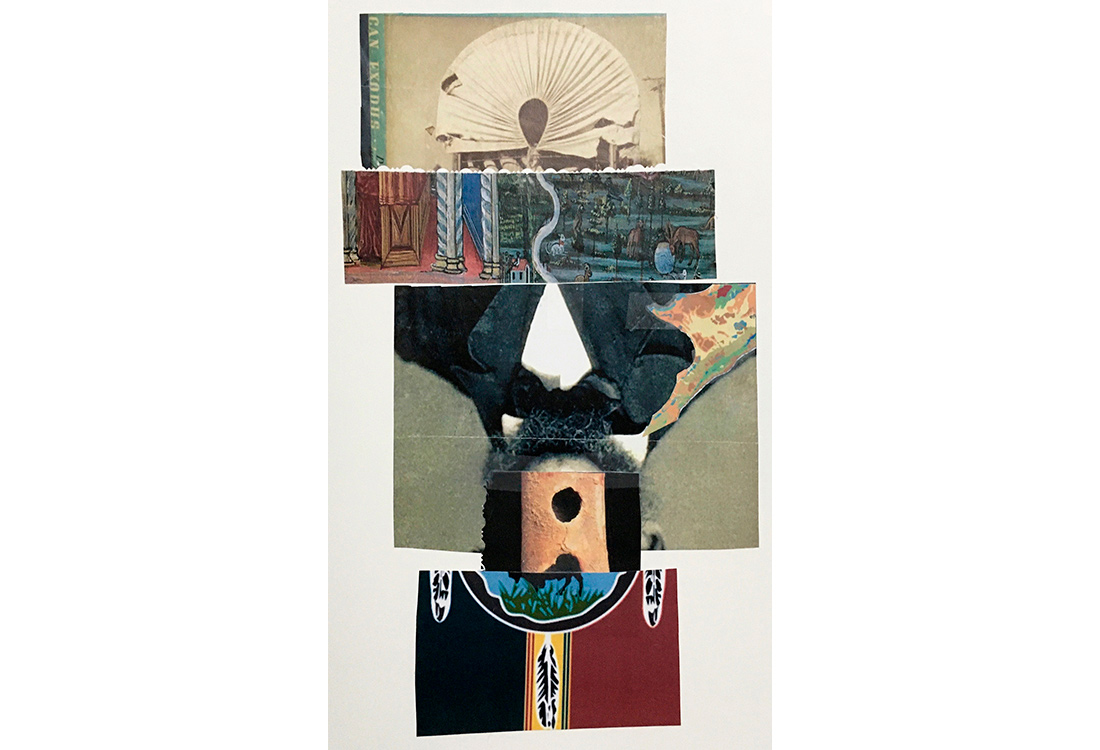

40 / 70 | “Carlisle newspaper” (1906). The Indian school of Carlisle Pennsylvania (1879–1918) was the first of many away from family schools set on quickly and firmly assimilating and training native children to the disciplines of an agricultural lifestyle. Plowing, mining and damming were alien concepts to their customs and were considered inflicting loss and damage to nature. Quote: “Plow deep while sluggards sleep and you’ll have corn to sell and keep”.

-

43 / 70 | Marie Tharp (Michigan, 1920–2006) was a geologist and cartographer and was the first to scientifically map the ocean floor. Women at the time were not allowed to work aboard ocean vessels so Tharp used the data collected to systematically map the ocean floor back at home. She took thousands of sonar readings and literally drew the deep underwater details of the ocean floor. “Not too many people can say this about their lives: I had a blank canvas to fill with extraordinary possibilities, a fascinating jigsaw puzzle to piece together: mapping the world’s vast hidden seafloor. It was a once-in-a-lifetime—a once-in-the-history-of-the-world—opportunity for anyone, but especially for a woman in the 1940s. The nature of the times, the state of the science, and events large and small, logical and illogical, combined to make it all happen”.

-

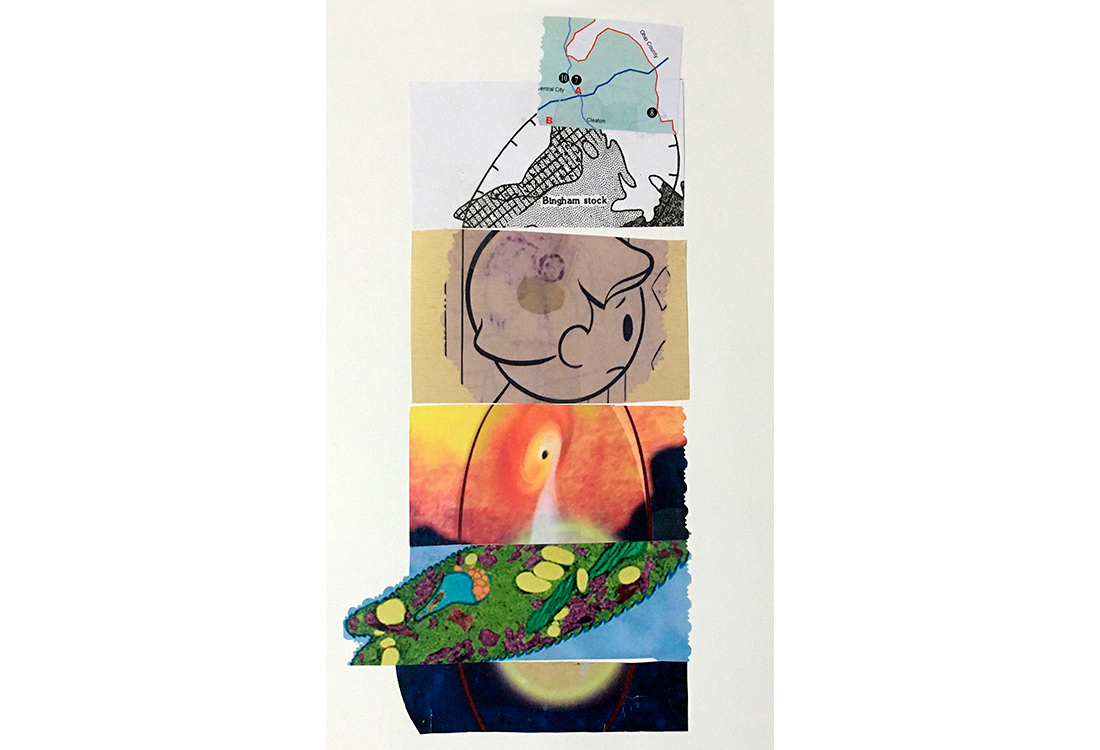

45 / 70 | The Berkeley Pit is a former copper mine located in Butte, Montana, United States. It is 1 mi (1,600 m) long by 1⁄2 mi (800 m) wide with an approximate depth of 1,780 feet (540 m). It is filled to a depth of about 900 feet (270 m) with water that is heavily acidic. The mine was opened in 1955 until its closure in 1982 when the water pumps in the nearby Kelley Mine were turned off, and groundwater from the surrounding aquifers began to slowly fill rising at about the rate of 1 foot a month. A $19 million treatment facility was completed in August 2019 and the first discharge of treated water into a local creek happened in October 2019. Researchers studying the water composition, discovered a robust, single-celled algae known as “Euglena Mutabilis”, thriving in the toxic waste. Intense competition for the limited resources caused these species to evolve the production of highly toxic compounds some of which have shown to fight against cancer cells. This is a good example of how we make a lot of money fast then must spend even more money to remedy the exploitation of the environment and dangers it causes to ourselves. Then in searching for remedies our destruction turns into researching how nature responds to extreme environments, and helps us to find ways to live amongst our own toxic waste.

-

49 / 70 | Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Shovels (1965). Kosuth belongs to a broadly international generation of conceptual artists that began to emerge in the mid-1960s. His work consisted of an object, a photograph of it and dictionary definitions of the words denoting it. “That celebrated marriage of science, art and photography seemed, at the time to join together how we see the world-art with how we were coming to know it-science”.

-

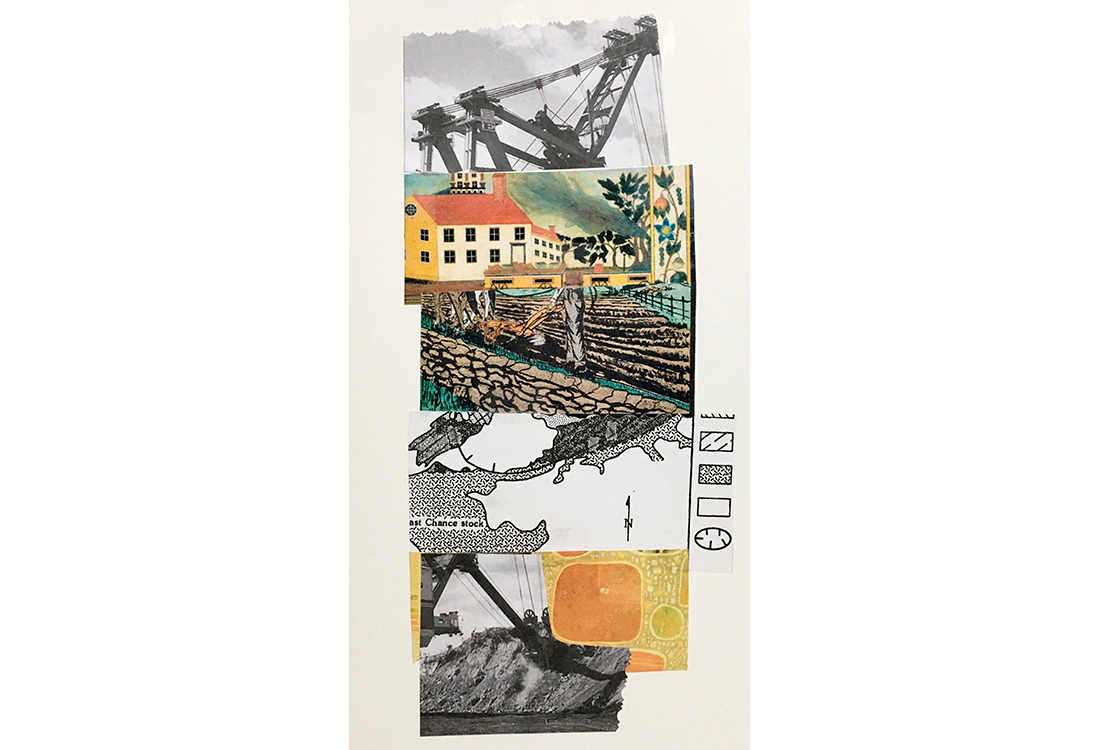

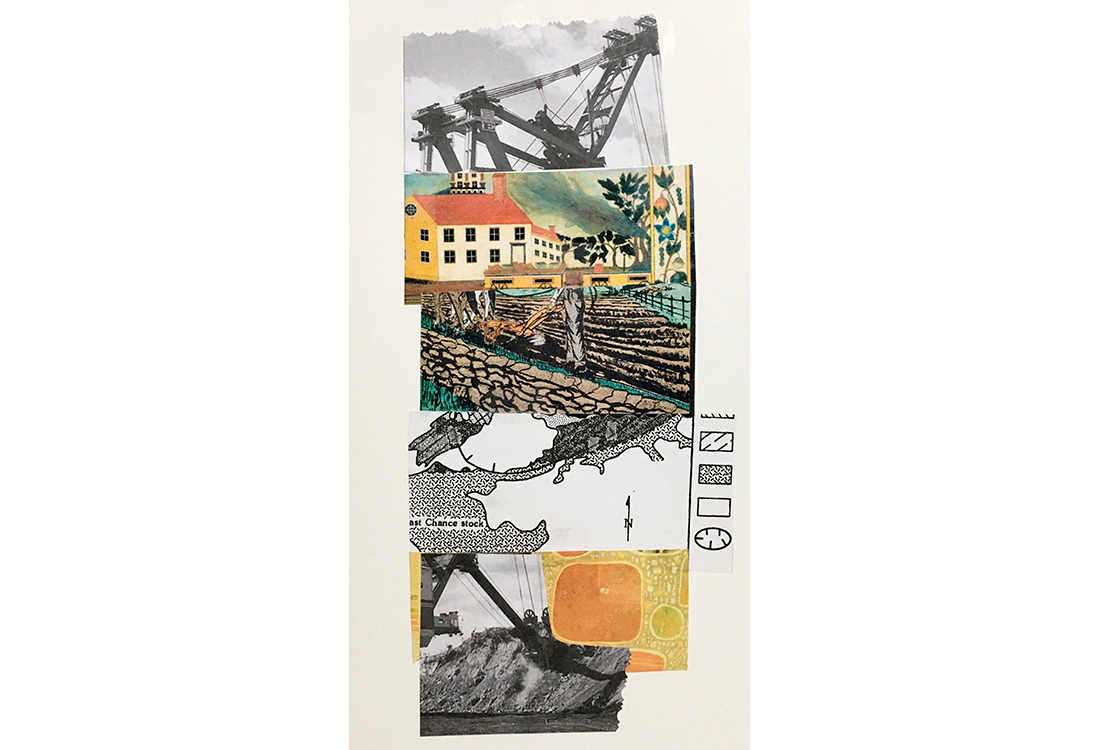

51 / 70 | The Bucyrus Erie 3850-B Power Shovel named “Big Hog” went to work next door to Paradise Fossil Plant for Peabody Coal Company’s Sinclair Surface Mine in 1962. When it started work it was received with grand fanfare and was the Largest Shovel in The World with a bucket size of 115 cubic yards. This technological “star” churned through thousands of acres of Muhlenberg County land that laid above the coal seams there. After it finished work in the mid 1980’s, it was buried in a pit on the mine’s property. It remains there still today. A strange twist for a grand digger that ended up “digging” its own grave (maybe it went to Paradise?)!

-

53 / 70 | Seamus Heaney: “Death of a Naturalist” (1966). “Under my window, a clean rasping sound when the spade sinks into gravelly ground: My father, digging. The cold smell of potato mold, the squelch and slap of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge through living roots awaken in my head. But I’ve no spade to follow men like them. Between my finger and my thumb, the squat pen rests. I’ll dig with it”.

-

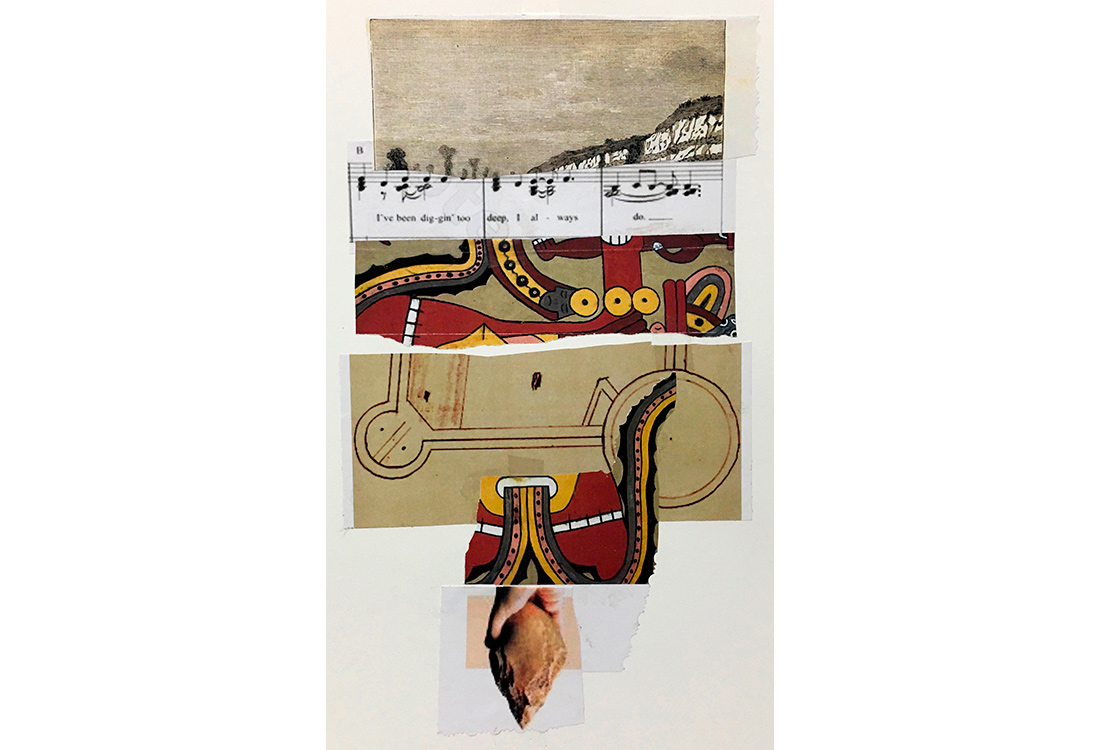

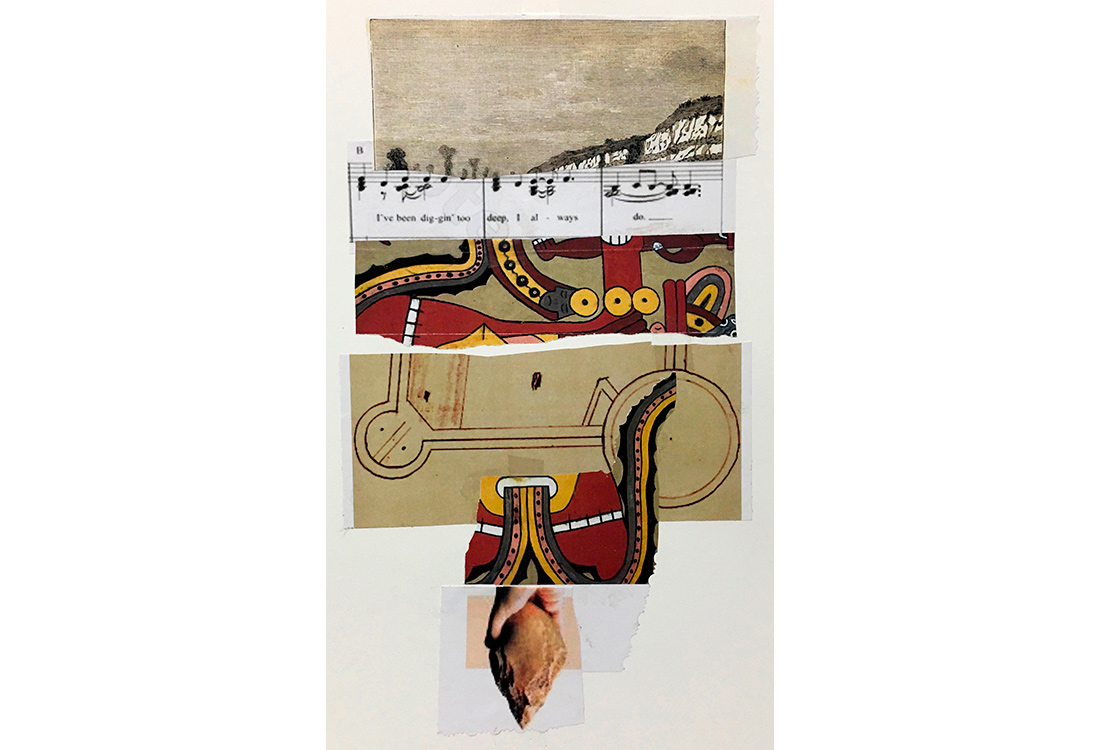

62 / 70 | “Hammer and Nail” (1990), Virgin Songs Inc. and GODHAP Music, words and music by Emily Ann Saliers. “A blistered hand on the handle of a shovel / I’ve been digging too deep, I always do / Gotta tend the earth if you want a rose… / I started seeing the whole as a sum of its parts”.

-

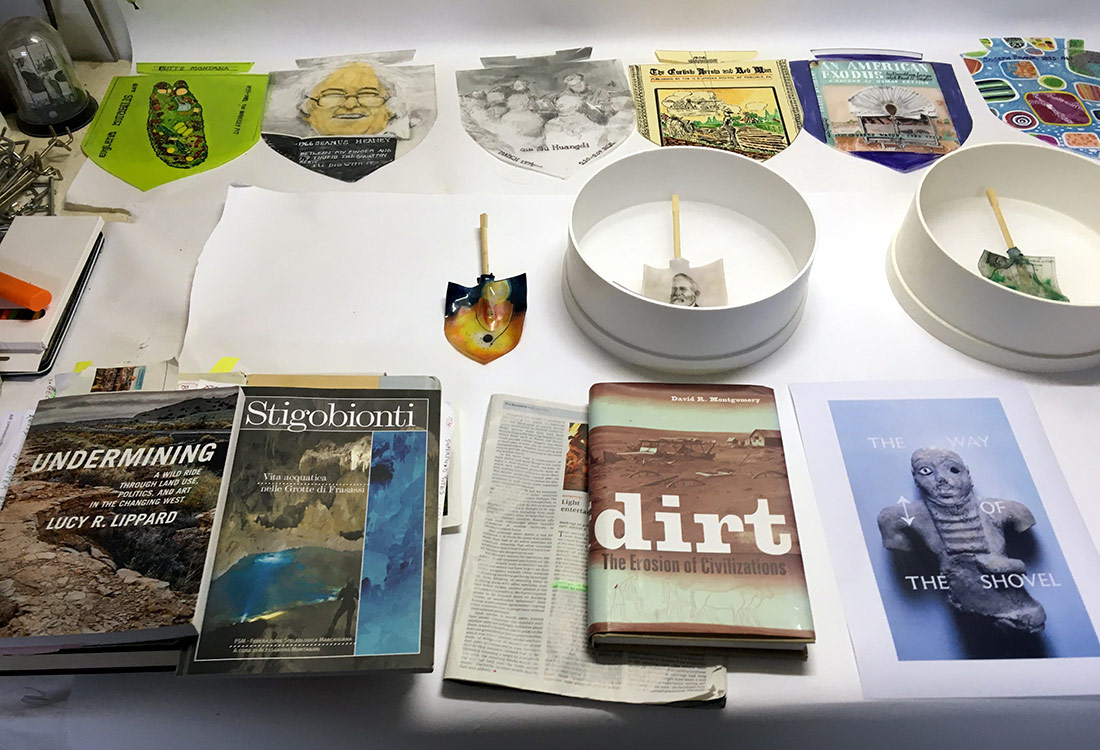

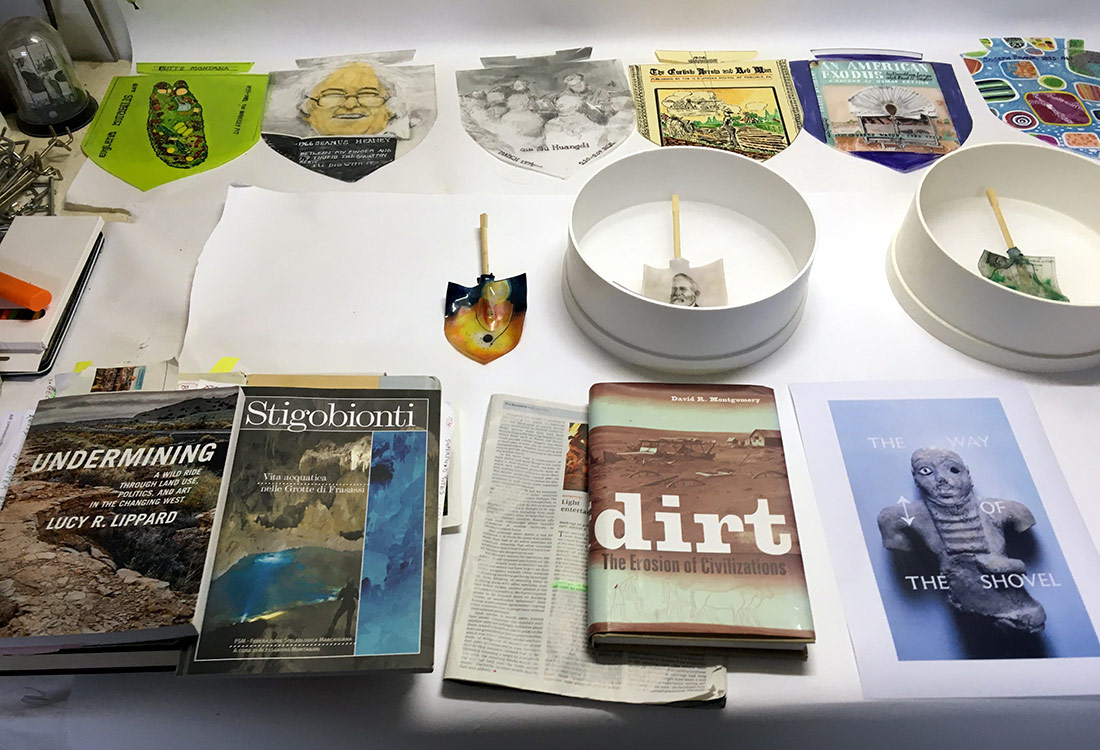

63 / 70 | Lucy R. Lippard (born April 14, 1937), American writer, art critic, activist and curator. The weft of her text is deeply entwined with Land; Land as place and identity, land as Mother Nature, how land has been imagined, captured and (ab)used. She has been a persistent advocate of excavating the dirty truths about human’s damage to the earth’s surface and how we have eroded the foundation of rock formation, damaged and weakened gradually and insidiously. Her years of hard work contain a mine of information. I dedicate this shovel to her task.

-

68 / 70 | Leanne Wijnsma, a Dutch artist, feels there is too much choice in our urban societies. To escape the stress, she started to hand-dig small holes and climb inside. “Escape, 2022, is an action triggered by the paradox of freedom. It is a response to this world in which we are always connected, always available. It is an urge to do something really banal yet essential. The hole doesn’t lead to freedom. The choice to dig however becomes the freedom itself”. She is interested in creating experiences for our senses, trusting that instinct evokes an inherent truth.

-

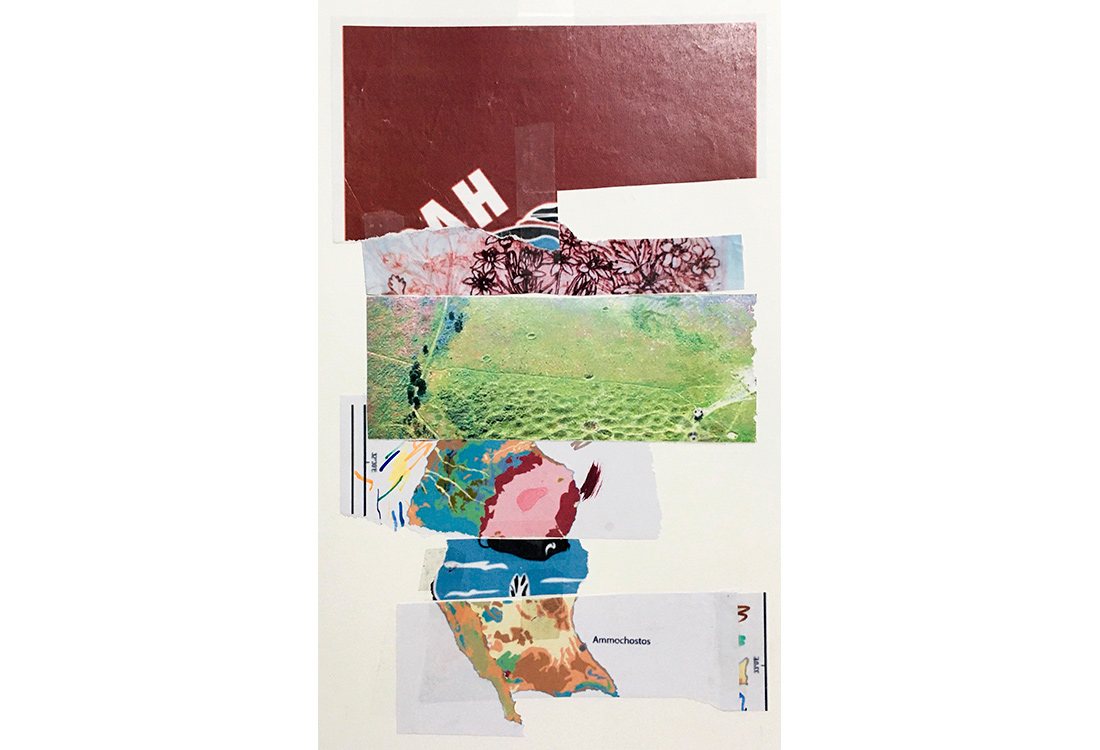

70 / 70 | Esther Quaedackers (2023) is a Lecturer in “Big History” at the University of Amsterdam, where she has been developing, coordinating, and teaching big history courses for over a decade. She is the inventor of the ‘little big history’ approach, which is a research and teaching method in which small subjects are connected to aspects of big history. It also enables students to envision the future in an interconnected/interdisciplinary way, thinking about many subjects relevant to our world. This shovel demonstrates a teaching model of different levels of complexity, (material, biological, cultural) that have histories of different lengths, material history being the longest, cultural history being the shortest, but all extending up to the present. The stacking helps to research the interactions between the levels, exploring the connections, and so leading to new knowledge that has not been explored. The layered model feels like digging into deeper levels and then popping up from the hole, an up and down, back and forth journey.

-

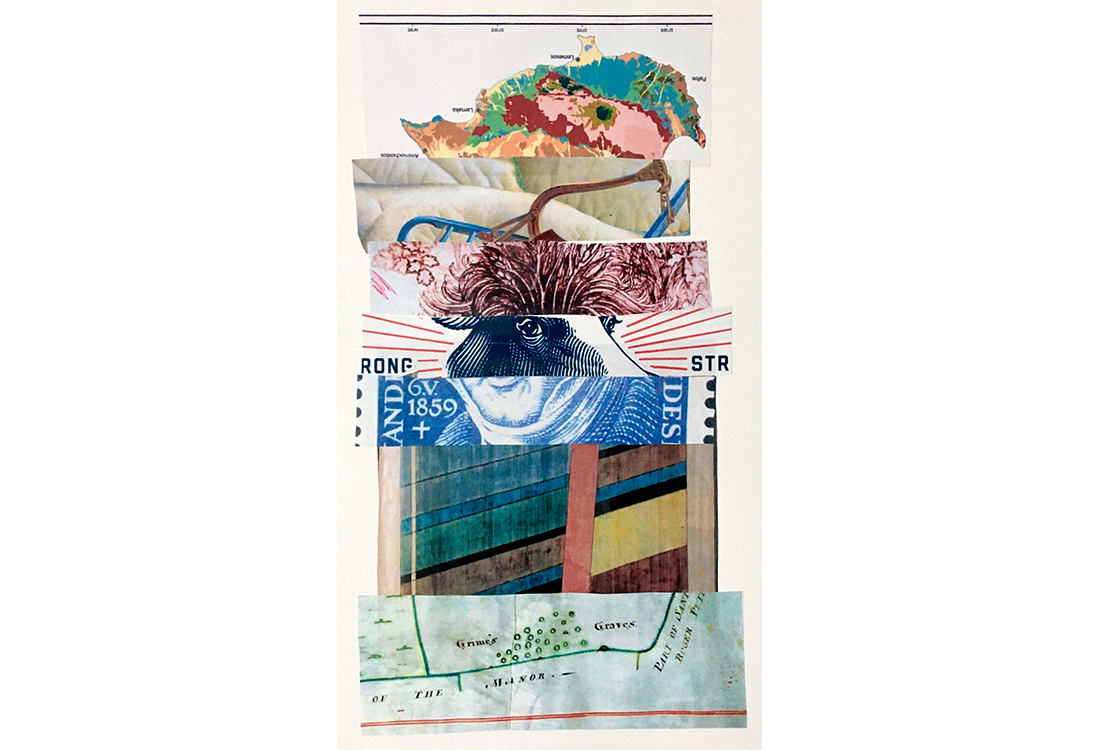

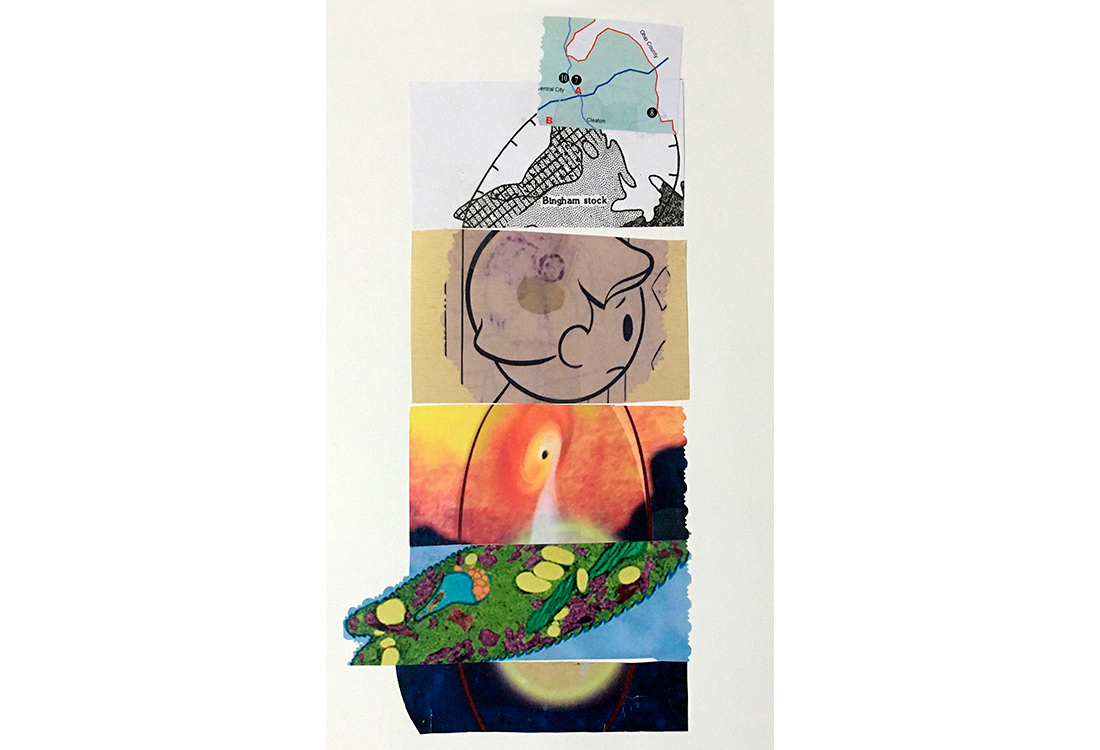

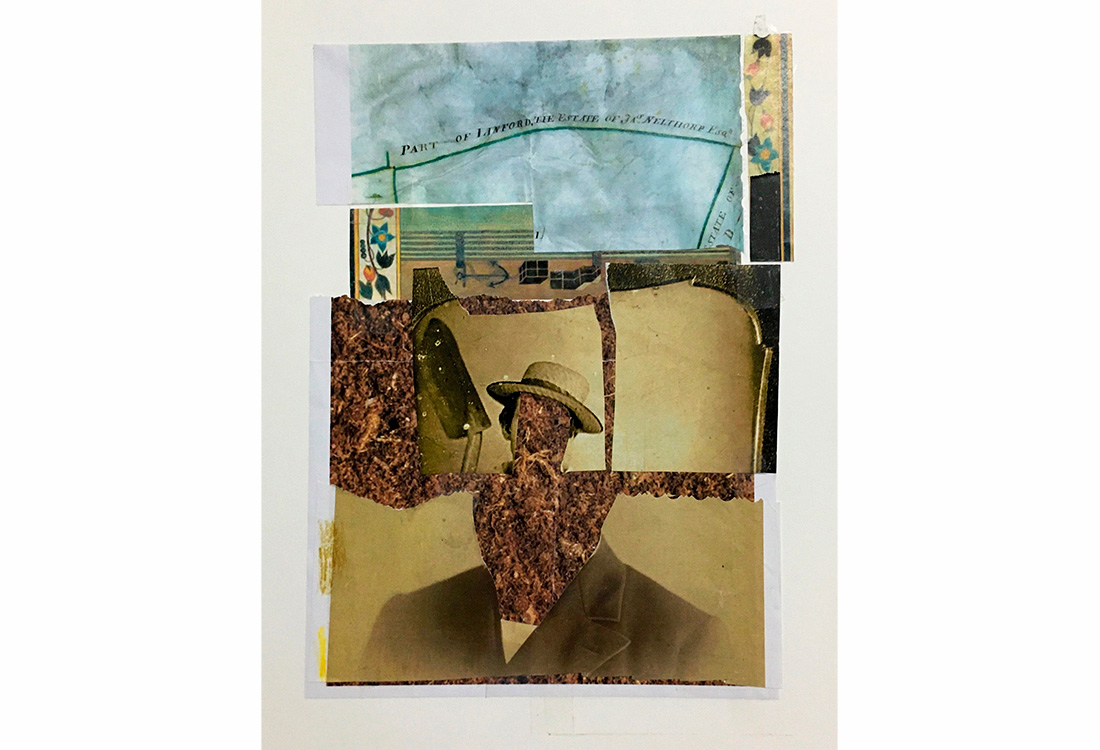

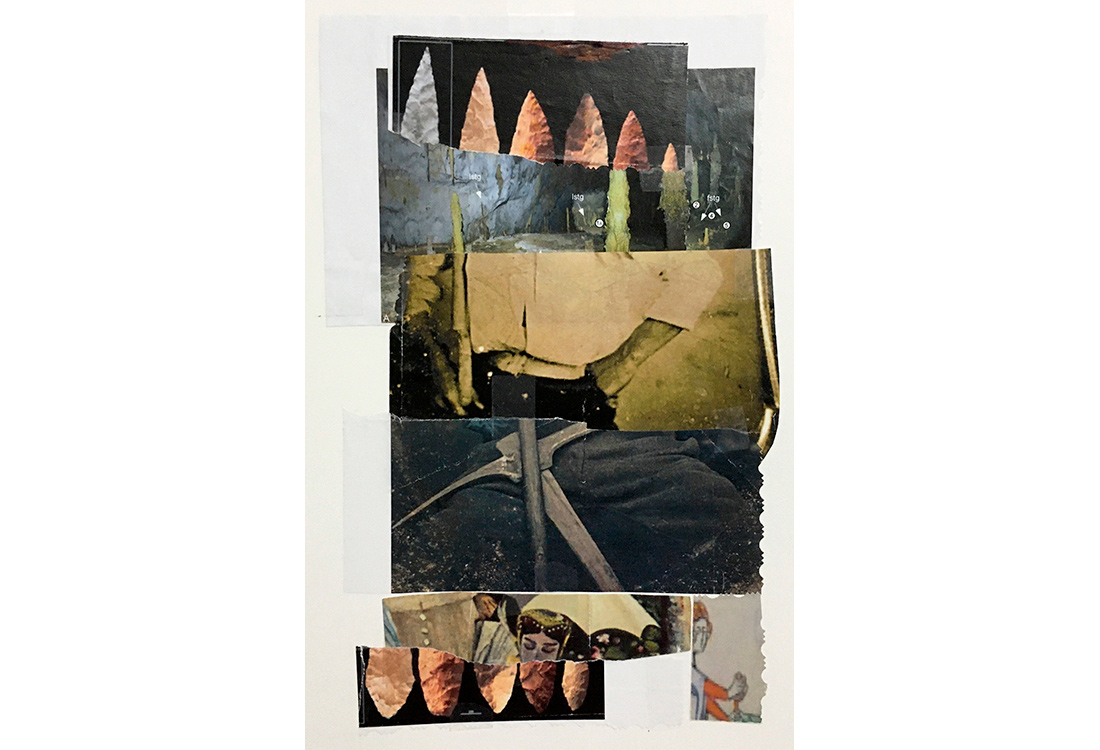

Work in progress.

-

Work in progress.

-

Work in progress.

-

Work in progress.

-

#1 thin section.

-

#2 thin section.

-

#3 thin section.

-

#4 thin section.

-

#5 thin section.

-

#6 thin section.

-

#7 thin section.

-

#8 thin section.

-

#9 thin section.

-

#10 thin section.

-